A popular version of the Christkind

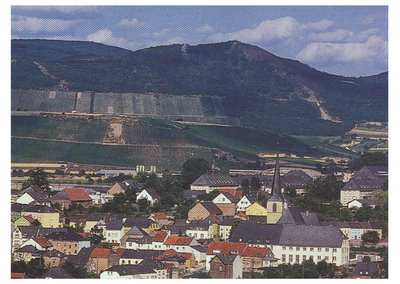

Oberzerf, the home village of my Rauls ancestors was at the edge of the Hunsrück region in what was then Kreis Saarburg. Since my great-great grandmother, Magdalena Rauls, was born on December 25, I have a special interest in the Christmas customs of her village in 1827. The closest I have come so far is the small book called, "Die Hunsrücker Küche," (Hunsrück cooking) by Christiane Becker. Along with recipes for traditional Christmas treats, there is a description of some of the Christmas customs of the Hunsrück of the last century.

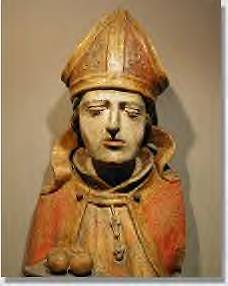

A figure of St. Nicholas from the 13th century

But first, a little history. The eve of the feast of St. Nicholas on Dec 6 was originally the time when children in German-speaking regions received gifts. Saint Nicholas was clothed in a bishop's red robe, somewhat like today's Santa Claus or Weihnachtsman. On his head was a miter, and he carried the staff of a bishop of the Catholic Church. Martin Luther urged his followers to stop this custom which had such strong Catholic church connections. The Christ child, he preached, gave the greatest gift to mankind, and children should receive presents from him on the day that commemorates his birth. The change began in the northern regions where the majority of the population was Lutheran, but by the nineteenth century, even in the Catholic regions, the Christkind brought gifts on Christmas eve. However St. Nicholas retained his popularity in the Catholic areas, continuing to bring presents on St. Nicholas eve. (There is more information on the celebration and customs of St. Nicholas eve in my archived post from January 2006).

Literally translated, the word "Christkind" means Christ child. However, in the 19th century, the Christkind was not represented by a babe in a manger but rather by an angelic figure with golden wings and long blond hair. In some parts of Germany, especially Bavaria, teenage girls clothed in white dresses and wearing golden wings played the Christkind, but customs varied. Christiane Becker, author of "Die Hunsrücker Küche," describes the Christkind custom in the small village of Götzeroth in the Idarwald as follows: On Christmas eve, the Christkind, face covered with a veil, went from house to house, accompanied by the "Stabbegloose", two figures in black clothes and hats. Both carried a staff and hid their black painted faces behind a beard of flax. The raccous sounds of staffs and bells were eagerly awaited by the children because the trio were bringing gifts. The Stabbegloose would push their boisterous way into each house in the village, followed by the Christkind. As a reward for their turbulent visit, they were rewarded with money or, in earlier times, with Kuchen. The actual visit of the Christkind was done in fewer and fewer places as the 19th century progressed, and today such a custom is a rarity.

Baking for Christmas was done during the season of Advent. At sunset in December when the sky was a shimmering red, there was an old saying in the Hunsrück: "The Christkind is baking sugar cookies." The women and children of the family were busy making familiar Christmas recipes. The aroma from the kitchen, which had been turned into a virtual bake shop, permeated the whole house. Naturally, there was quite a bit of tasting of the Zuckerblätjer, as the cookies were called in the Hunsrück dialect. But the Zuckerblätjer soon disappeared into cans and glass jars, to await Christmas eve. There were nut cookies, Lebkuchen, spritz cookies, cinnamon wafers, and chocolate balls in the recipe box of Becker's grandmother.

Except in rare exceptions like the one mentioned above, the Christkind was not seen by the children. He brought the gifts and trimmed the Christmas tree behind a locked door in the good room of the home, aided by parents and sometimes also by grandparents and relatives. The curious children waited impatiently for the door to open, but by the time the Christmas bells were rung and the door was flung wide, the Christkind had gone.