The Hochzeitlader, "Der Blumenbaum, Jan., Feb., Mar., 2005

After a brief interruption for Martini I’m back to the subject of 19th century wedding customs, this time those of Bavaria. (Upon rereading that sentence, it sounds as if I've been having some liquid refreshment. Actualy, there is another kind of "martini" which is described in my previous post.)

Background

In 1984 I went to Eastern Bavaria with a second cousin on my mother’s side of the family to visit the little villages where our Probst ancestors had lived. When I dragged cousin Allen into a bookstore in the city of Regen, I gravitated toward a book with pretty pictures titled, Der Landkreis Regen: Heimat im Bayerischen Wald, and didn’t worry about the content. At that time the only German I knew was “Der Bleistift ist auf dem Tisch” (The pencil is on the table). An opportunity to read that phrase did not occur very often. But as so often has happened to me when I am on German soil, I had the good luck to pick a book with fantastic information in it.

As soon as I learned to read some German, I realized I had brought home a detailed word picture of life in Eastern Bavaria as well as a pretty picture book. In 1858, Bavaria’s King Maximilian II ordered the district medical officer in each Landkreis (administrative district) to send him an account of his subjects. It was to contain a description of their physical attributes, their clothes, their housing, the way they earned their living, even their customs and celebrations. Here was a king with an uncommon curiosity about the people he ruled.

A number of these written manuscripts were preserved and stored in the Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek (Bavarian State Library) in Munich. The reports about the Eastern Bavarian districts of Viechtach and Regen were translated by Dr. Reinhard Haller in a chapter called “Ethnographische Beschreibung der Landgerichte Viechtach und Regen aus den Jahren 1858-1860.” The report contained words that no longer exist in regular German dictionaries, which made me unsure of my translation. Help arrived in the form of an article in “Der Blumenbaum,” the magazine published by the Sacramento German Genealogy Society. An article about marriage customs in the mountains of Bavaria, “A Wedding in the Mountains,” was an English language description of very similar customs to the ones I was struggling to understand. In addition to the text, it reproduced pictures from a little book called “A Hochzeit im Gebirg.”

The Engagement

As in the Hunsrück, the prospective bridegroom came to look over the property of the bride’s father and, if his proposal was accepted, the bride-to-be cooked her first meal for him. In Bavaria, this dish was called “Schmarrn”, a popular Bavarian specialty that is a cross between a pancake and an omelet. When it is cooked, it is cut up and sprinkled with powdered sugar.

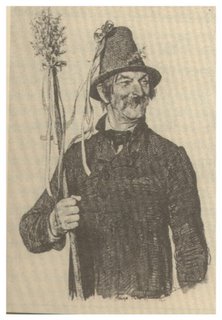

Soon after the second announcement of the marriage banns were called in the church, the Hochzeitslader or wedding inviter began his rounds with the bridegroom. All the relatives had to be invited, and the father of the groom might travel along to make sure none of the distant relatives or acquaintances were missed. The Hochzeitlader’s hat was decorated with rosemary and a cluster of flowers. On his left arm he wore a circle of artificial flowers, and he carried a Hochzeit ramrod (the rod used to push down gunpowder into old-fashioned weapons). To show its peaceful purpose for this occasion, it was decorated with many colorful silk ribbons.

Kammerwagon (bedroom wagon) photo, Der Landkreis Regen in alten Ansichten

Shortly before the wedding ceremony, the bride’s possessions had to be transported to her new home. This was done with as much public display as possible, especially if the bride’s family was well to do. A wagon, loaded with furniture, linens, and whatever finery the bride was bringing to her home, was driven slowly through the village, giving everyone a chance to observe and comment.

The Wedding Day

The wedding itself usually took place in the late morning. As in Normandy and in the Hunsrück, there was a procession to the church, sometimes with musicians leading the way. The equivalent of today's bridesmaid and best man led the bride to the altar.

After the religious ceremony, the entire party made its way to the Gasthaus which, according to the article in “Der Blumenbaum,” was almost always located close by the church. Here a family would provide as fine a meal as their financial situation would allow. Those who were invited but who could not attend because of infirmity or farm duties were not overlooked. They received food packets, sent with friends or relatives and often wrapped in the women’s scarves.

After the wedding meal, it was time for the Hochzeitlader to perform his duties as master of ceremonies. The bride and groom usually sat at a special table that was covered with a white cloth. With them would be the Ehrenvater and Ehrenmutter. These were very honored guests, often a godparent or a grandparent of the bride or groom. The Hochzeitlader called the guests one by one to the table, announcing them with a polite phrase or sometimes a comic insult. There might be an appropriate flourish by the musicians as the family name was called, and guests were called in the order of their relationship to the bridal couple. Once at the table they would drink from the glasses of the bride and the groom and lay down the Mahlgeld, a contribution toward the expense of the meal as well as a wedding gift. Sometimes a well-to-do farmer would make a show of sprinkling just a few coppers or silver pennies in front of the bride and groom. As he turned away from the table he would surreptitiously slide his hand into his pocket, turn back to the table with his fist full of valuable Taler, pleased with his little joke.

When it is time for the dancing to begin, the newly married couple had the first dance. The Hochzeitlader was again in charge, deciding who, in turn, would be next to come to the dance floor. And he decided when it is time for the guests to go home. When he told the band to play the Rausschmeisser (literally translated it would be called "The Bouncer"), a piece of music that was known to everyone as the tune which ended the dancing, the celebration was over.

No comments:

Post a Comment