|

| Wedding Document from Hunsruck |

|

| Barge Stop on the Saar |

|

| Zerf farm life shown in village museum - horn planters |

|

| Saarburg mill stream |

On June 24 I celebrated an anniversary of sorts - my 7th full year of written posts for "Village Life in Kreis Saarburg". That means that this blog post begins year eight! When I wrote that first post, seven years seemed an impossibly long time to continue my project; now it seems impossible that the time has gone so fast. As these early posts are probably the most neglected, it seems fitting to bring them to the forefront again as part of my personal anniversary observance and as examples of ways to learn family history from less used sources.

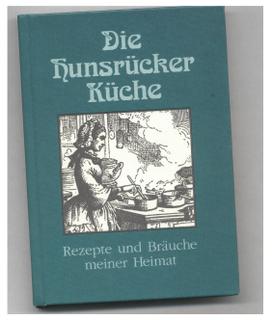

My very first post on this blog was about Easter customs in the Hunsrück area of Germany. I bought a small recipe book, self-published, in a bookstore and it was a treasure. In searching for traditional recipes my ancestors might have enjoyed, i found not only recipes for Easter dinner, but also a gold mine of information about the traditions that went along with the recipes. For instance, children began to gather moss from the forests about two weeks before Easter so that they would have enough for a soft nest. The night before Easter, the moss nests were carefully placed in the garden, thus inviting the Easter Hase to lay its eggs there. But what if it rained on the evening of Easter Saturday? The children brought the nests inside and placed them in the kitchen, using a little willow basket to help keep the moss in nest-shape form. Recipe books can be a great source of information!

My next four posts were written about a visit to a small village museum in Zerf, Germany. This dusty little museum was crammed full of farm implements, furniture for the living spaces, tools, baskets and buckets carried to the fields, harnesses for the ox, horse, or cow. There was even a reconstructed stone bake oven. That museum was the labor of love of one man in the village. When he died, the museum was kept closed unless one applied for permission to see it. The mayor kept the key in his office. Luck was with me when I visited because a local resident procured my entry. I had a guided tour from the mayor and his wife, and was given a guide to items in the museum. Because they knew I was coming, the mayor's wife had hand typed it especially for me. Through the blog, I was able to share that guide, along with the pictures I took, since much of what was inside that large room would be very similar to other village museums all over Germany. And there are many almost-forgotten museums in every state in the United States. When visiting the places where ancestors lived for a time, it is wise to ask if there is an almost forgotten museum. One of my favorite souvenirs of that day in Zerf was the tiny wooden peg I was given. Such pegs were used in place of a nail by the shoemaker when constructing the sole of a shoe.

I wrote three posts about wedding customs. My little Hunsrück recipe book - mentioned above - had the ingredients for traditional dishes served at a wedding meal in a location near Kreis Saarburg, Germany. It also included some traditional Hunsrück wedding customs in addition to the recipes for wedding dishes. On two other visits to Europe, I had stumbled across books that included the wedding lore of Normandy and weddings in Bavaria. So I included two other posts as a comparison to the Hunsrück wedding celebration. It was interesting that very far-flung areas had many baptism, marriage and death ceremonies and customs that were similar, something good to know when one is unable to find the "perfect" social history of the ancestors' town. A lot of the birth, marriage and death rituals in other parts of Germany, especially if the same religion was practiced, can be described (with proper notation) when writing a family history. There is more chance of being right than being wrong.

The history of Saarburg, Germany, which is the equivalent of a county seat in the US, was the subject of another early post. A German city which is designated a Kreis is one where the officials, who were a step above the local mayors, had offices and where most of the residents of the small villages had to travel when legal matters complicated their lives. The growing middles classes were likely to live in the Kreis or county seat in the 19th century. There were also owners of mills, tanneries, inns, and a great number of shopkeepers, since a city that could call itself a Kreis was a market town for cattle, produce, etc. My ancestors, I am sure, made a trip or three to Saarburg, sometimes to buy what they could not barter in their small village; or to sell produce. After the market closed for the day, there was an opportunity for the visiting villagers to observe the way of life in the "big city"- in what to them must have been a place of fascination. While there may not be that special book about your ancestors villages, there undoubtedly is some published information about the county seat or a larger city nearby, whatever it was called.

My grandmother had told me that her grandfather was a sailor, a story I dismissed as fictitious until I grasped the concept that a sailor did not necessarily sail on the ocean. The men who transported cargo in the unglamorous barges going up and down the Saar River were also sailors/seamen. The craftsmanship and ability necessary to build and sail the barges was greatly respected in Saarburg and the neighboring villages. It was a proud profession passed down from one generation to another, and it is doubtful that grandma's grandfather, Johann Meier, came from one of these families. But was he a hired "sailor" or one of the Halfen? As if to lend credence to Grandma's story, Johann still owned his own coil of rope, the kind used for pulling the barges, which he sold to a sailor from Beurig before leaving for America. It's always wise to take family stories with a grain of salt, but don't overlook the kernel of truth in the process.

Some people believe that local customs have to be learned from the people who lived at the time. With today's quick-changing technology, it may seem that memories of the way life was lived told by parents or grandparents can't help much in recreating the lifestyle of great-grandparents and their parents. It's easy to forget that customs changed much more slowly even 50 years ago, and that a parent or relative or even a careful listener of one's own generation may have a head filled with details and tales a genealogist has never heard. All you have to do is ask. That's why I recorded every detail that Ewald Meyer and his wife Helena described about earlier times in their village of Irsch. Sometimes we were discussing customs from their lifetimes (more than a hundred years later than the period at which my great-great grandparents had lived there). It didn't take me long to realize that, from their reminiscing, I could learn about traditions which were observed in much earlier times. Using those notes, I wrote the blog post, "Of Apple Wine, Cabbage, and Other Everyday Things."

Yes, I've learned a lot about the Rhineland villages of my ancestors right from the beginning of my posting. Organizing my information well enough to make it clear to a reader often showed me anomalies that I would have missed otherwise, and even better, new thoughts occurred that put me on the track of more and more resources. Some of those documents and pictures I had never dreamed I would hold in my hands. And writing this post about my 2005 posts shocked me too. It reminded me how quickly I forget; how much I've already forgotten. Thank goodness for celebrating anniversaries!