Sections of pages 1 and 2 of a passenger list filed with New York port authorities on May 9, 1861

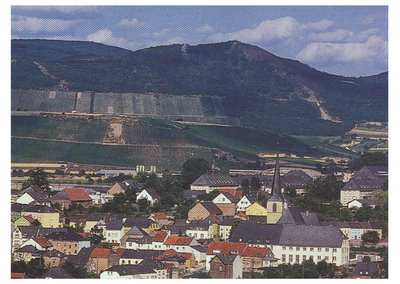

In my last post I wrote about the process of obtaining permission to emigrate. This time I want to focus on a special group of emigrants from the village of Irsch, Kreis Saarburg, Rheinland. These neighbors, some of them related to each other, had all made a decision to seek a better life for themselves and their children in America; and, when they received the necessary documents, they traveled to Wisconsin aboard the same sailing ship. Among them were my great-great grandparents, Johann and Magdalena Meier and their four children. Their fifth child, Anna Maria, was left behind in the cemetery beside the church.

What was it like, I wonder, to sell your farm and almost all of your possessions, close the door of the house you had lived in for many years, and walk beside a wagon or push a wheelbarrow loaded with just those few item that you had packed into a trunk or some sturdy cloth bags. These stoughthearted men and women must have asked themselves over and over, "Will these things that we carry with us be what we need to help us survive the ocean trip and the first months in the new country?"

Did these travelers wave goodbye to their neighbors and pause for a moment to scan the still-fallow fields that they would never plant again? Did this last sight of their village happen on a day that was cold and rainy; or was it a sunny morning, the breeze tinged with a spring warmth?

While I have no way to prove it, I think it is likely that the people I am talking about not only traveled on the same ship; but also made the trip from Irsch to Le Havre together. If so, they probably boarded the train at the stop in Beurig and went on to Metz via Saarbrucken. In Metz, they changed trains in order to travel on to Paris. In Paris, one of Europe's largest and most cosmopolitan cities, these inexperienced villagers either transfered to yet another train or took a steamer up the Seine River to reach the port city of Le Havre.

The thirty emigrants whose names are recorded on the passenger list of the American ship Rattler (second page of the two documents above) were a mixed lot, ranging in age from over 50 to just one year old. There were four farmers, a wagon maker, a serving maid, and a day laborer. Six of the children listed were over 18 years of age - old enough to be a productive part of the workforce that the sparsely settled state of Wisconsin was seeking.

The Group of Thirty:

1. Maria Feilen, 23 years old, serving maid. She had received her permission to emigrate on February 22, 1861.

2. Heinrich Britten, 55 years old, farmer. He received emigration permision on February 25, 1861. He and his family settled in St. John/Hilbert, Wisconsin.

3. Elizabeth Mertes Britten, wife of Heinrich Britten, 51 years old.

4. Peter Britten, 20 years old son of Heinrich and Elizabeth Britten.

5. Michel Britten, 18 years old, son of Heinrich and Elizabeth Britten.

6. Margaretha Britten, 8 years old, daughter of Heinrich and Elizabeth Britten.

7. Maria Britten, 7 years old, daughter of Heinrich and Elizabeth Britten.

8. Peter Hein, 30 years old, day laborer. He received permission to emigrate on February 25, 1861. He and his wife and daughter settled in St. John /Hilbert, Wisconsin.

9. Anna Britten Hein, wife of Peter Hein, 29 years old (daughter of Heinrich and Elizabeth Britten - see previous entry)

10. Elizabeth Britten, daughter of Anna and Peter Hein, 4 years old.

11. Michel Meier, 50 years old, unmarried farmer, uncle of #25, Johann Meier. He received his permission papers on February 27 1861 and settled in St. John, Wisconsin

12. Peter Lauer, 38 years old, wagon maker. He and his family received permission to emigrate on 2 March 1861. They settled in Fussville, Wisconsin which is now a part of Menomonee Falls, Waukesha County, Wisconsin.

13. Magdalena Wagner Lauer, wife of Peter Lauer, 37 years old.

14. Margarethe Lauer, daughter of Peter and Magdalena Lauer, five years old,

15. Johannes Lauer, son of Peter and Magdalena Lauer, two years old.

16. Mathias Fisch, 48 years old, farmer. He received his permission to emigrate on January 31, 1861. He wanted to leave, he said, because acquaintances living in American had convinced him that he could support his family better there. He settled in St. John, Wisconsin

17. Magdalena Lauer Fisch, 48 years old, wife of Mathias Fisch.

18. Magdalena Fisch, daughter of Mathias and Magdalena Fisch, 25 years old.

19. Johann Fisch, son of Mathias and Magdalena Fisch, 21 years old. He had served in the Hohenzollerschen Regiment, Nr. 40 in Saarlouis, according to information in the Koblenz Staatarchiv.

20. Michel Fisch, 20 years old, son of Mathias and Magdalena Fisch.

21. Jakob Fisch, 15 years old, son of Mathias and Magdalena Fisch.

22. Nikolaus Fisch, 13 years old, son of Mathias and Magdalena Fisch.

23. Maria Fisch, 10 years old, daughter of Mathias and Magdalena Fisch.

24. Peter Fisch, 8 years old, son of Mathias and Magdalena Fisch.

25. Johann Meier, 35 years old, farmer. He and his family received emigration permission on March 5, 1861. His reason for leaving..."that he already had two brother-in-laws there and was going to them." (One of these men was his wife's brother, Mathias Rauls, who had settled in Dane County Wisconsin about 1857.) Johann Meier and his family settled in St. John, Wisconsin.

26. Magdalena Rauls Meier, 33 years old, wife of Johann Meier.

27. Mathias Meier, 11 years old, son of Johann and Magdalena Meier

28. Anna Meier, 9 years old, daughter of Johann and Magdalena Meier

29. Johann Meier, 3 years old, son of Johann and Magdalena Meier

30. Michel Meier, one year old, son of Johann and Magdalena Meier

Early in April 1861, these thirty men, women, and children boarded the American sailing vessel, Rattler, which would take them across the Atlantic Ocean to the port of New York. Under the leadership of Captain Almay and his crew, they would live in the steerage area between decks for 32 days. By the time they stepped ashore in New York City on May 9, soldiers in dark blue Union uniform were everywhere. The American Civil War had just begun.